One of the most common criticisms about NFTs relates to their massive environmental cost. Many proponents argue there are now “eco-friendly” blockchains that solve all problems pertaining to electricity use and emissions – but is that actually the case? In this section, we explain the true environmental cost of NFTs and discuss how the term “eco-friendly”, when used to describe a blockchain, is frequently misused and manipulated to suit those who stand to gain most from legitimizing and perpetuating that particular blockchain, and is not reflective of the reality of the environmental and social costs.

What is it about NFTs that receives eco-criticism?

NFTs are built on the blockchain. Every time an NFT is added to the blockchain or its ownership is transferred to someone else, that transaction needs to be verified. In order to verify transactions, different blockchains employ different strategies called consensus mechanisms. We explain this in more detail in the Non-Technical Blockchain Explanation. There are two primary systems for generating consensus – Proof of Work (PoW) and Proof of Stake (PoS) – both of which expend computing power to accomplish this task, with the former consuming drastically more energy than the latter.

Proof of Work

Proof of Work, the consensus system underlying both Bitcoin and Ethereum, is inefficient by design. In this system, in order to validate a block of transactions, groups of high-power, specialized computers race against each other to guess a really big number that solves a puzzle. The first to solve the puzzle receives a reward, and all the transactions in that block are added to the blockchain. All excess work is discarded, and the machines that lost immediately move on to trying to solve another puzzle to verify more transactions.

Not only is this process incredibly wasteful and inefficient – it is wasteful and inefficient by design to discourage bad actors. Additionally, to make these currencies deflationary, the puzzles also intentionally become more complex over time, which leads more energy to be consumed and thus more emissions produced as time goes on. The profitability of mining depends on the energy consumed per hash (source).

For Bitcoin, on top of this massive energy consumption, miners must use the latest specialized processors to compete equally against other miners. This has resulted in the proliferation of ASICs (Application Specific Integrated Circuit) – processors that serve little use outside of Proof of Work blockchain mining. This competition creates massive amounts of e-waste, as these ASICs are really only designed to be useful for cryptocurrency mining. The estimated average service life of mining hardware is less than 16 months, not counting embedded carbon emissions from its manufacture, transport, and disposal. (source) (source) While Ethereum was intended to be ASIC-resistant, its ecosystem has also seen a rise in specialized hardware designed purely for Ethereum mining, sharing the same e-waste problems as Bitcoin.

Proof-of-Work is a relatively simple concept, but when scaled into a trillion-dollar cryptocurrency chain has an unsustainable carbon footprint (source). Combined, all of these attributes stand together to make Proof of Work truly terrible for the environment.

But how bad is it, really?

At the time of writing, BAD.

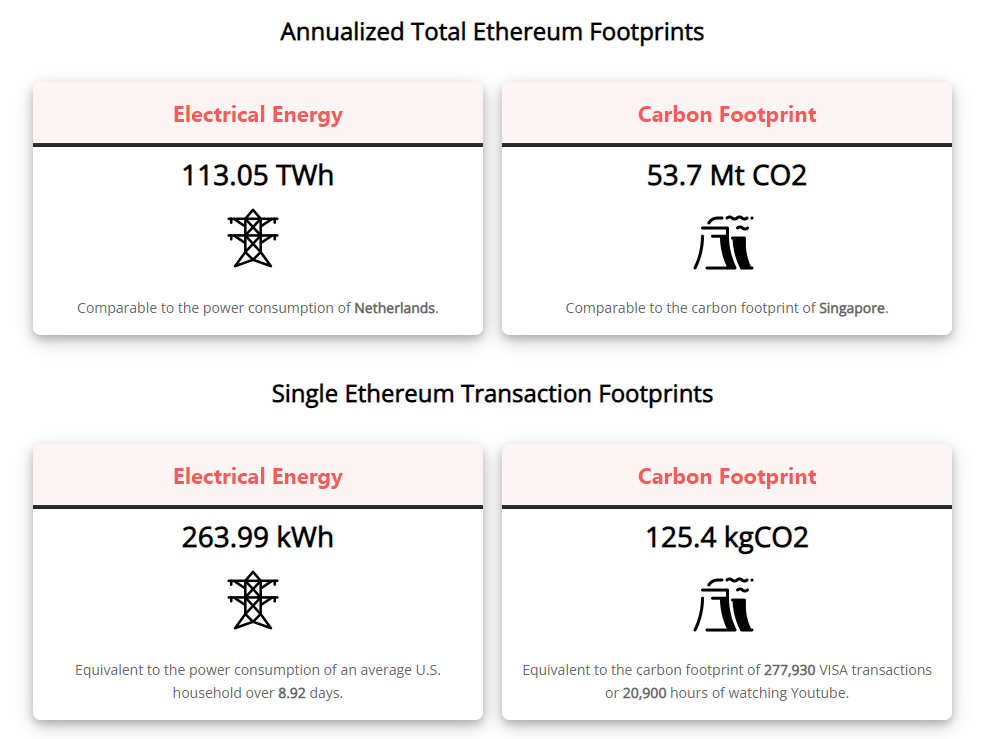

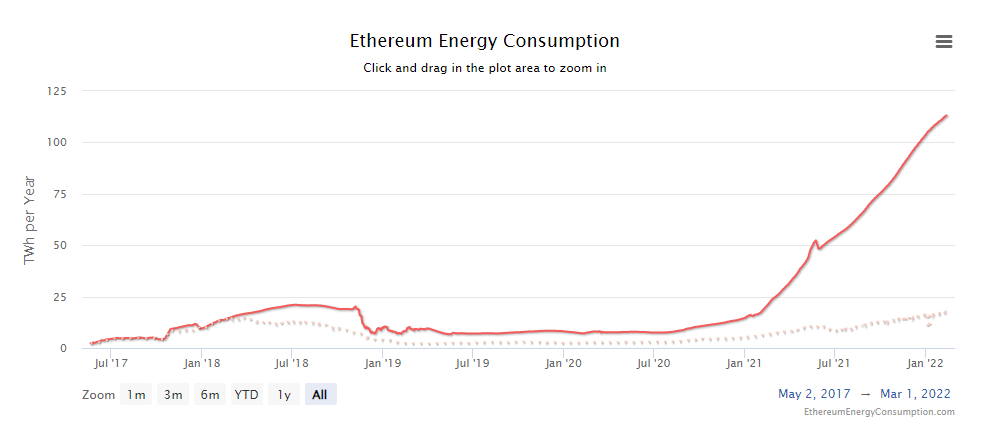

As Digiconomist explains in their report, the estimated energy consumption of the Ethereum grid continues to grow steadily in spite of growing awareness of its massive environmental impact:

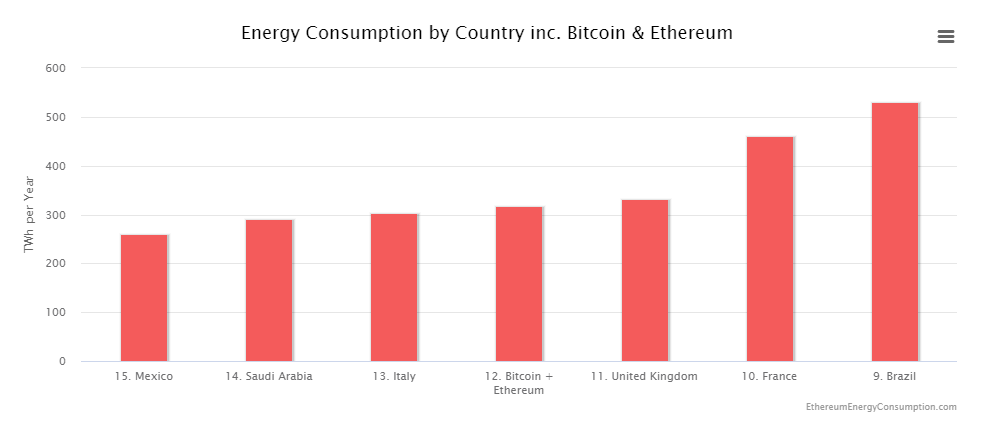

In fact, at the time of writing, if Bitcoin and Ethereum were one country, estimates put their combined emissions at 12th in the world.

According to the Ethereum wiki, a new block is added to the blockchain every 12 seconds or so for security purposes, meaning the blockchain is constantly requiring energy intensive work to be performed. A common misconception is that because this energy inefficient mining will be performed regardless of whether there are transactions to be processed or not, NFTs aren’t actually contributing to the problem at all!

This is similar to the argument that because a flight will happen whether you are on it or not, you are therefore not adding any additional emissions by flying. While your individual contribution to the flight emissions may be small, flights are offered on a supply-and-demand basis. More demand in seats on planes results in more flights and higher ticket prices.

Both flying and Ethereum operate on supply-and-demand. Due to this, a higher demand on the Ethereum network (like, say, due to the growing popularity of NFTs) can lead to higher fees and increased energy usage and emissions due to an uptick in transactions.

It is impossible to know exactly how much energy is consumed by any one cryptocurrency, and even more challenging to know how much of that usage can be attributed to NFTs – as the demand of all cryptocurrencies has increased in lockstep with NFT hype.

On top of this, it’s common for crypto enthusiasts to argue that because it costs so much to run crypto mining operations, these miners are incentivized to mine where electricity is cheapest – suggesting that miners are incentivized to use renewable energy wherever possible. One glaring problem with this argument, however, is that the cheapest available energy sources in many countries are still not renewables. After China banned crypto mining, many miners fled to Kazakhstan, where they overwhelmed the coal-powered grid to the point of failure. Not to mention the fact that there are countless socially valuable uses for renewable energy and power in general that risk getting pushed out due to demand from miners.

Another pro-mining argument is that mining operations can utilize excess energy from renewables when demand is low and energy would otherwise be wasted, and then yield energy back to the grid when demand is high. Their argument rests on the idea that miners will do this simply because the cost for them would outweigh how much they earn. Given how cheap renewables have become, and how highly-valued Bitcoin and Ethereum have been in recent months, this is a shaky argument at best.

Overall, it’s impossible to know how much crypto mining is performed using renewable energy at any given time. It’s also impossible to know exactly how much of that energy would’ve gone to use elsewhere in the grid for all instances. That doesn’t mean the estimates shared above are totally off, however, and the growing energy consumption and subsequent emissions of these Proof of Work cryptocurrencies should alarm everyone involved.

But other things are worse! Look at how bad the gaming industry is already!

True! The gaming industry is a significant contributor of global greenhouse gas emissions. In fact, Climate Replay exists because we see a massive opportunity for game companies to reduce their environmental impact and help create a better world.

Often, proponents of NFTs and crypto will compare Ethereum or Bitcoin to the global banking industry, stating factually that the global banking industry produces more emissions than these crypto currencies do.

This is also true! However – the global banking industry serves almost 8 billion people with their everyday necessities, while these cryptocurrencies serve a few hundred thousand people who are mostly transacting trying to capitalize on the speculative value of these currencies while the market is hot.

In one oft-cited essay by crypto fan and design engineer Sterling Crispin makes the following assessment:

What I’m saying is that if these digital artists were selling enough shirts, photo books, and other physical merch to make the same amount of money there wouldn’t be a single article or headline written about the negative impact.

In this analogy, every physical product purchased is a reminder to that artist that they have a fan who wants to support them. With NFTs – there will always be that question…is the buyer supporting me and my art, or are they just trying to make money off it like any other speculative commodity? But Crispin raises a fair point – emissions of purchased physical goods don’t get criticized nearly as much as they should. Ultimately, what should be criticized is all emissions. We should be scrutinizing the emissions of every product, every corporation, every chance we get. But we need to start somewhere, and as shown above, NFTs and cryptocurrencies are far more problematic per transaction than existing methods for supporting purchases of products and services.

One final note here – we recognize that many existing systems are not optimized or as efficient as we might like them to be. Unfortunately, changing many of these systems would require monumental effort, both time-wise and financially. As we have seen, cutting emissions has proven quite challenging within our current economic structure. It is much more feasible to say no to a new technology that we do not need than it is to change an existing widely-adopted technology, even though in an ideal world we should be both optimizing and upgrading existing technology and rejecting unnecessary new forms of technology.

Eco-friendly blockchains and Proof of Stake to the rescue?

Ethereum has been saying they will move to PoS from the energy-intensive PoW for years. Their conservative estimates claim this switch will reduce emissions of their blockchain by 99.5%.

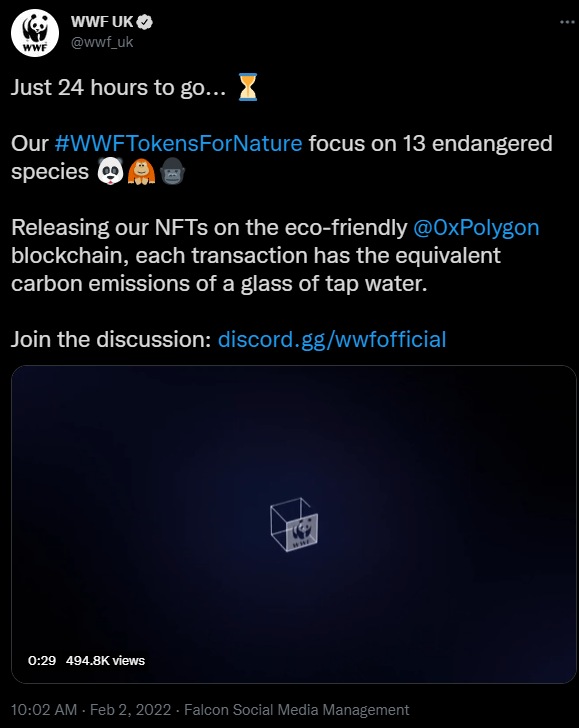

Similar claims about Proof of Stake are applied when speaking about sidechains like Polygon or Ethereum competitors such as Tezos, which many proponents of NFTs use to claim that the ecological problems of crypto and NFTs are now “solved.” However, Polygon and other sidechains to Ethereum still require Ethereum to exist and perpetuate due to their algorithmic dependency on the Ethereum “mainnet” and heavy use of ETH as a cryptocurrency within their own networks. The Verge explains this dependency and the subsequent emissions extremely well in this article.

Frustratingly, in Polygon’s own marketing, they deliberately ignore or mask their reliance on Ethereum and advertise only the costs of the PoS blockchain as if it were independent of Ethereum (and thus claim to be “eco-friendly”). Digiconomist estimates that a Polygon transaction produces approximately 2,100 (!!!) times more emissions than WWF advertised in their recent short-lived NFT campaign. While still not as bad as an average Proof of Work transaction, 430g of CO2 per transaction is a far cry from the “glass of tap water” WWF advertised on behalf of Polygon.

Independent PoS blockchains such as Tezos do exist, but are nowhere near as popular as Ethereum, so it is uncertain how their total emissions will change with time.

It is merely a happy coincidence being exploited for a positive public image that Proof of Stake happens to consume less energy, and is thus less environmentally harmful than Proof of Work. Ultimately, optimizations made to these blockchains are not in the interests of the planet, but in the profits of the people using them. By reducing the amount of work needed to process transactions, they are reducing the fees they need to pay per transaction, which helps owners maximize profits. Any additional benefits for the planet are merely victories for the reputations of these systems.

As PoS doesn’t typically require industrial amounts of electricity to process transactions, they advertise that they are eco-friendly in comparison. Ethereum, however, after switching to Proof of Stake, will require 128 validators to sign off on every block, with at least 2/3rds of validators agreeing on the end result. Ethereum’s upcoming switch at one point had 200,000 users vying to become validators. That is a lot of computers vying to verify transactions relying on a switch that hasn’t even happened yet.

Regardless of the future, we have to acknowledge reality as it stands right now:

- The majority of NFTs use Ethereum or Ethereum sidechains that are still dependent on Ethereum

- The individual value of an NFT depends on the general market value of NFTs as a concept and the value of Ethereum and cryptocurrency in general

- Ethereum still uses Proof of Work, with an annualized electricity consumption on the scale of a medium-sized industrial nation.

- NFTs are one of the main purchases that holders of ETH can make, and as such are popular transactions

- Transfers from ETH to other blockchain cryptocurrencies require significant transaction fees, so there is low motivation for ETH holders to switch to PoS competitors

- Promoting NFTs as a concept, no matter what blockchain is used, contributes to the sustained perceived market value of NFTs.

- The market value of NFTs being high leads to an increase in demand which leads to an increase in how much work is required to process transactions on the Ethereum blockchain

- More work required to process a transaction results in more energy consumption

- More energy consumption results in more emissions

Ultimately, while the total energy consumption of Proof of Stake is significantly lower than that of Proof of Work, the sad truth remains: the value of all cryptocurrencies and NFTs is tied intrinsically to spent physical resources.

The Honest Truth

“During unprecedented temperature increases, sea level rise, the total loss of permanent sea ice, widespread species extinction, countless severe weather events, and all the other hallmarks of total climate collapse, this kind of gleeful wastefulness is, and I am not being hyperbolic, a crime against humanity.” – Everest Pipkin

There is no such thing as an “eco-friendly” blockchain

At best, this term is simply good PR, effectively saying “we’re so much better than the horrendously bad situation [Proof of Work] that currently exists that we can call ourselves good for the environment by comparison.”

The uncomfortable truth, put so eloquently into words by Everest Pipkin, reminds us that any system where value is determined by the amount of energy wasted is not sustainable:

A value system that understands itself only in terms of what, materially, has been burned so far to create investment and what, materially, will need to be burned tomorrow is one that is untenable to the future we have to build, one that has decoupled worth with waste, one where units of labor are not bought and sold for wage.

At their core, even the most “accessible” staking systems in Proof of Stake are out of reach for our planet’s most vulnerable populations. In Ethereum 2.0, a validator is required to have 32 ETH (currently ~ $93,000) to stake, at minimum – an expensive participation entry cost. If we’re serious about tackling the climate crisis, and if these cryptocurrencies are serious about helping those who need it most, any proposals for how to handle currency in the future need to be built on the idea of providing opportunity for all, especially those most vulnerable, not rewarding wealth to those who produce the most waste. To quote Everest one more time:

…climate justice must mean giving leadership and power to those who will bear the worst effects of climate catastrophe, including the very young, those living in the global south, those living rurally in coastal areas or farming regions, those living in poverty, those in marginalized communities, and particularly to indigenous communities who have actual experience in managing complex local ecosystems for generations without creating spiraling, resource-extractive devastation.

As long as these cryptocurrencies are being designed, implemented, and owned primarily by those who have little understanding of the multitude of issues faced by disenfranchised communities, they will, at their core, move us further from solving the multitude of issues that have led us to the current climate and ecological crisis we are in.

The World Wildlife Fund recently found out the hard way that the environmental implications of NFTs extend far beyond the direct emissions produced as a result of the work put into minting an NFT. Even the lowest-energy Proof of Stake blockchains ultimately perpetuate a system that puts us in a worse situation than before when it comes to global emissions, climate justice, and income inequality.

Ultimately, we are in a CLIMATE CRISIS. We have less than a decade to reduce emissions drastically or we risk setting off irreversible, catastrophic chain reactions. All emissions that we don’t need to emit, we shouldn’t emit. There is no “eco-friendly” silver bullet when it comes to blockchains, and certainly not when it comes to NFTs either.